Ulfilas (Wulfila in Germanic), A.D. 311–383, missionary to the West-Goths in the Balkan region; founder of Arianic-Germanic Christendom, who translated the Bible into Gothic.

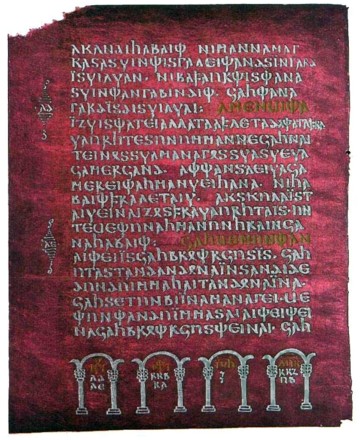

Codex Argenteus

location: Uppsala, Universitetsbibliotek [Sign. DG. 1]

size: 187 leaves (originally 336 leaves)

content: Parts of the Gospels in the order Matthew, John, Luke, Mark.

Splendid manuscript written in silver and gold ink on purple parchment, also known as the Silver Bible (Swedish Silverbibeln). Presumably written in Italy in the early 6th century. First discovered in the sixteenth century in the monastery of Werden (Germany). Subsequently taken to Prague (Rudolf II), captured by the Swedes (1648) and brought to Stockholm, taken to Holland by Isaac Vossius and finally bought by Magnus Gabriel De la Gardie, who donated the manuscript to the University of Uppsala (1669).

”

Anyone who follows the spread of Eastern Christianity and the spread of Arianism can see a Mithras element in it, even though in already quite weakened form. Any translation of the Ulfilas-Bible into modern languages remains imperfect if one is unaware that Mithras elements still play into the terminology of Ulfilas (or Wulfila). But who pays heed nowadays to these deeper relationships in the linguistic element? As late as in the fourth century, there were philosophers in Greece who worked on bringing the ancient etheric astronomy into harmony with Christianity. From this effort then arose the true Gnosis, which was thoroughly eradicated by later Christianity, so that only a few fragments of the literary samples of this Gnosis have remained.

What do people really know today about the Gnosis, of which they say in their ignorance that our anthroposophy is a warmed-over version? Even if this were true, such people would not be able to know about it, for they are familiar only with those parts of the Gnosis that are found in the critical, Occidental-Christian texts dealing with the Gnosis. They know the quotes from Gnostic texts left behind by the opponents of the Gnosis. There is hardly anything left of the Gnosis except what could be described by the following comparison. Imagine that Herr von Gleich would be successful in rooting out the whole of anthroposophical literature and nothing would remain except his quotations. Then, later on, somebody would attempt to reconstruct anthroposophy based on these quotes; then, it would be about the same procedure in the West as that which was applied to the Gnosis. Therefore, if people say that modern anthroposophy imitates the Gnosis, they would not know it even if it were the case, because they are unfamiliar with the Gnosis, knowing of it only through its opponents.

So, particularly in Athens, a school of wisdom existed well into the fourth century, and indeed even longer, that endeavored to bring the ancient etheric astronomy into harmony with Christianity. The last remnants of this view — man’s entering from higher worlds through the planetary sphere into the earth sphere — still illuminate the writings of Origen; they even shine through the texts of the Greek Church Fathers. Everywhere one can see it shimmer through. It shines through particularly in the writings of the genuine Dionysius the Areopagite. This Dionysius left behind a teaching that was a pure synthesis of the etheric astronomy and the element dwelling in Christianity. He taught that the forces localized, as it were, astronomically and cosmically in the sun entered into the earth sphere in Christ through the man Jesus of Nazareth and that thereby a certain previously nonexistent relationship came into being between the earth and all the higher hierarchies, the hierarchies of the Angels, of Wisdom, the hierarchies of the Thrones and the Seraphim, and so on. It was a penetration of this teaching of the hierarchies with etheric astronomy that could be found in the original Dionysius the Areopagite.” — Rudolf Steiner, Materialism and the Task of Anthroposophy, lecture 4, 15Apr1921, Dornach, GA 204

“

We must realise the importance of this world-historic event. Ancient culture is still alive in Augustine’s environment, but it is already decadent, has passed into its period of decline. He struggles bitterly, but to no purpose, with the last remnants of this culture surviving in Manichæism and Neoplatonism. His mind is steeped in what this wisdom, even in its decadence, has to offer, and, to begin with, he cannot accept Christianity. He stands there, an eminent rhetorician and Neoplatonist, but torn with gnawing doubt. And what happens? Just when he has reached the point of doubting truth itself, of losing his bearings altogether along the tortuous paths of the decadent learning of antiquity in the fourth century of our era, when innumerable questions are hurtling through his mind, he thinks he hears the voice of a child calling to him from the next garden: ‘Take and read! Take and read!’ And he turns to the New Testament, to the Epistles of St. Paul, and is led through the voice of the child to Roman Catholicism.

The mind of Augustine is laden with the oriental wisdom which had now become decadent in the West. He is a typical representative of this learning and then, suddenly, through the voice of a child, he becomes the paramount influence in subsequent centuries. No actual break occurs until the fifteenth century and it may truly be said that the ultimate outcome of this break appears as the change that took place in the life of thought in the middle of the nineteenth century.

And so, in this fourth century of our era, we find the human mind involved in the complicated network of Western culture but also in an element which constitutes the starting-point of a new impulse. It is an impulse that mingles with what has come over from the East and from the seemingly barbarian peoples by whom Roman civilisation was gradually superseded, but whose instructors, after they had mingled with the peasantry and the landowning classes, were the priests of the Roman Church. In the depths, however, there is something else at work. Out of the raw, unpolished soul of these peoples there emerges an element of lofty, archaic spirituality. There could be no more striking example of this than the bock that has remained as a memorial of the ancient Goths — Wulfila’s translation of the Bible. We must try to unfold a sensitive understanding of the language used in this translation of the Bible. The Lord’s Prayer, to take one example, is built up, fragment by fragment, out of the confusion of thought of which Augustine was so typical a representative. Wulfila’s translation of the Bible is the offspring of an archaic form of thought, of Arian Christianity as opposed to the Athanasian Christianity of Augustine.

Perhaps more strongly than anywhere else, we can feel in Wulfila’s translation of the Bible how deeply the pagan thought of antiquity is permeated with Arian Christianity. Something that is pregnant with inner life echoes down to us from these barbarian peoples and their culture, to which the civilisation of ancient Rome was giving place. The Lord’s Prayer rendered by Wulfila, is as follows:

Atta unsar thu in himinam,

Veihnai namo thein;

Quimai thiudinassus theins.

Vairthai vilja theins, sve in himina, jah ana aerthai.

Hlaif unsarana thana sinteinan, gif uns himma daga.

Jah aflet uns, thatei skulans sijaima, svasve jah veis afletam thaim skulam unsaraim.

Jah ni briggais uns in fraistubnjai, ak lausei uns af thamma ubilin.

Unte theina ist thiu dangardi, jah mahts, jah vulthus in aivius. Amen.

Atta unsar thu in himinam, veihnai namo thein; Quimai thiudinassus theins. Vairthai vilja theins, sve in himina, jah ana aerthai. — The words of this wonderful prayer cannot really be translated literally into our modern language, but they may be rendered thus:

We feel Thee above in the Spirit-Heights, All Father of men.

May Thy Name be hallowed.

May Thy Kingdom come to us.

May Thy Will be supreme, an the Earth even as it is in Heaven.

— We must be able to feel what these words express. Men were aware of the existence of a primordial Being, of the All-sustaining Father of humanity in the heights of spiritual existence. They pictured Hirn with their faculties of ancient clairvoyance as the invisible, super-sensible King who rules His Kingdom as no earthly King. Among the Goths this Being was venerated as King and their veneration was proclaimed in the words : Atta unsar thu in himinam.

This primordial Being was venerated in His three aspects: May Thy Name be hallowed. ‘Name’ — as a study of Sanscrit will show — implied the outer manifestation or revelation of the Being, as a man reveals himself in his body. ‘Kingdom’ was the supreme Power: Veihnai namo thein; Quimai thiudinassus theins, Vairthai vilja theins, sve in himina, jah ana aerthai.

‘Will’ indicated the Spirit shining through the Power and the Name. — Thus as they gazed upwards, men beheld the Spirit of the super-sensible worlds in His three-fold aspect. To this Spirit they paid veneration in the words :

Jah ana aerthai.

Hlaif unsarana thana sinteinan, gif uns himma daga.

— So may it be on Earth. Even as Thy Name, the form in which Thou art outwardly manifest, shall be holy, so may that which in us becomes outwardly manifest and must daily be renewed, be radiant with spiritual light. We must try to understand the meaning of the Gothic word Hlaif, from which Leib (Leib=body) is derived. In saying the words, ‘Give us this day our daily bread,’ we have no feeling for what the word Hlaif denoted here: — Even as Thy ‘Name’ denotes thy body, so too may our body be spiritualised, subsisting as it does through the food which it receives and transmutes.

The prayer speaks then of the ‘Kingdom’ that is to reign supreme from the super-sensible worlds, and so leads on to the social order among men. In this super-sensible ‘Kingdom’ men are not debtors one of another. The word debt among the Goths means debt in the moral as well as in the physical, social life.

And so the prayer passes from the ‘Name’ to the ‘Kingdom’, from the bodily manifestation in the Spirit, to the ‘Kingdom’. And then from the outer, physical nature of the body to the element of soul in the social life and thence to the Spiritual.—

Jah aflet uns, thatei skulans sijaima, svasve jah

veis afletam thaim skulam unsaraim.

— May we not succumb to those forces which, proceeding from the body, lead the Spirit into darkness; deliver us from the evils by which the Spirit is cast into darkness. Jah ni briggais uns in fraistubnjai, ak lausei uns af thamma ubilin. — Deliver us from the evils arising when the Spirit sinks too deeply into the bodily nature.

Thus the second part of the prayer declares that the order reigning in the spiritual heights must be implicit in the social life upon Earth. And this is confirmed in the words : We will recognise this spiritual Order upon Earth.

Unte theina ist thiu dangardi, jah mahts, jah vulthus in aivius. Amen.

— All-Father, whose Name betokens the out er manifestation of the Spirit, whose Kingdom we will recognise, whose Will shall reign: May earthly nature too be full of Thee, and our body daily renewed through earthly nourishment. In our social life may we not be debtors one of another, but live as equals. May we stand firm in spirit and in body, and may the trinity in the social life of Earth be linked with the super-earthly Trinity. For the Supersensible shall reign, shall be Emperor and King. The Supersensible — not the material, not the personal — shall reign.

Unte theina ist thiu dangardi, jah mahts, jah vulthus in avius. Amen.

— For on Earth there is no thing, no being over which the rulership is not Thine. — Thine is the Power and the Light and the Glory, and the all-supreme Love between men in the social life.

The Trinity in the super-sensible world is thus to penetrate into and find expression in the social order of the Material world. And again, at the end, there is the confirmation: Yea, verily, we desire that this threefold order shall reign in the social life as it reigns with Thee in the heights: For Thine is the Kingdom, the Power and the revealed Glory. — Theina ist thiu dangardi, jah mahts, jah vulthus in aivius. Amen.

Such was the impulse living among the Goths. It mingled with those peasant peoples whose mental life is regarded by history as being almost negligible. But this impulse unfolded with increasing rapidity as we reach the time of the nineteenth century. It finally came to a climax and led on then to the fundamental change in thought and outlook of which we have heard in this lecture.

Such are the connections. — I have given only one example of how, without in any way distorting the facts, but rather drawing the real threads that bind them together, we can realise in history the existence of law higher than natural law can ever be. I wanted, in the first place, to describe the facts from the exoteric point of view. Later on we will consider their esoteric connections, for this will show us how events have shaped themselves in this period which stretches from the fourth century A.D. to our own age, and how the impulses of this epoch live within us still. We shall realise then that an understanding of these connections is essential to the attainment of true insight for our work and thought at the present time.” — Rudolf Steiner, European Spiritual Life in the 19th Century, Lecture 1, 15May1921, Dornach, GA 325